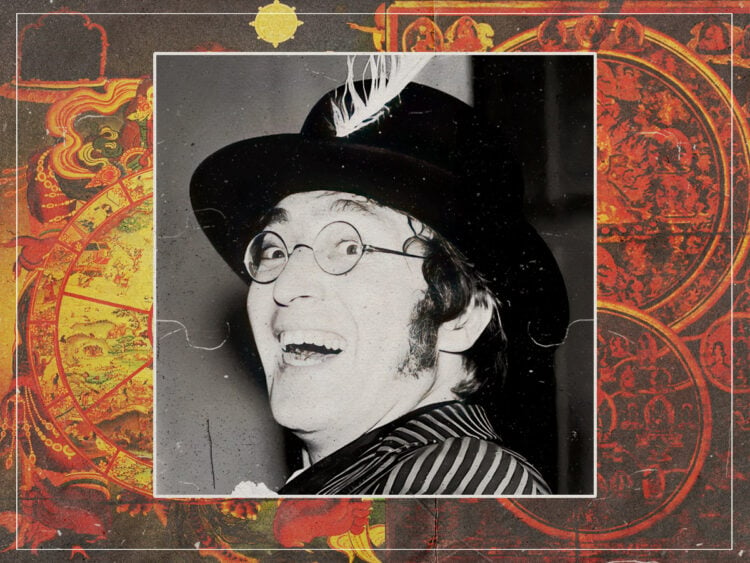

Bardo Thodol, commonly known in the West as The Tibetan Book of the Dead, is a comprehensive guide to living and dying. It’s a sacred text that proclaims: “May all sentient beings be endowed with happiness! May they all be separated from suffering and its causes! May they be endowed with joy, free from suffering! May they abide in equanimity, free from attachment or aversion.” And who can’t get behind that sentiment? It’s covered every unobtainable idealist box! John Lennon was bound to lap it up.

Nevertheless, its unburdened spiritualism has provided a crutch for many artists who have pored over its sacred pages. It is, quite simply, a guide to living well and facing up to mortality while you’re at it. As Graham Coleman’s translation cites: “The Tibetan Book of the Dead contains exquisitely written guidance and practices related to transforming our experience in daily life, on the processes of dying and the after-death state, and on how to help those who are dying. As originally intended this is as much a work for the living, as it is for those who wish to think beyond a mere conventional lifetime to a vastly greater and grander cycle.”

When new-age thinking came to the fore in the 1960s, Lennon figured he’d get in line with the times and ensure that The Beatles were at the forefront of the zeitgeist. Spiritualism, something the world seemed to need after JFK’s head was blown off and America hurtled into the Vietnam War, was the impetus for making art more expansive and littering pop with pertinent points to live by.

Lennon figured out a way to make it funky. “The final track on Revolver, ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, was definitely John’s,” Paul McCartney once recalled. “Round about this time people were starting to experiment with drugs, including LSD. John had got hold of Timothy Leary’s adaptation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead, which is a pretty interesting book.”

Wowed by the weird alternative, he wondered how he could manifest that within pop music. As Macca continues: “For the first time we got the idea that, as with ancient Egyptian practice, when you die you lie in state for a few days, and then some of your handmaidens come and prepare you for a huge voyage. Rather than the British version, in which you just pop your clogs. With LSD, this theme was all the more interesting.”

The book itself contains the classic line, “Whenever in doubt, turn off your mind, relax, float downstream,” which Lennon later transposed into the lyrics of his “first psychedelic anthem”. Lennon, however, learnt early on that spiritualism in music was best tempered with a sprinkling of sugar. As he said: “That’s me in my Tibetan Book of the Dead period. I took one of Ringo’s malapropisms as the title, to sort of take the edge off the heavy philosophical lyrics.”

He later did the same with ‘Imagine’, a track that envisages the whole world floating along in harmony. He applied the same poetic trick as Leary once again. He later said the track was “virtually the communist manifesto, even though I am not particularly a communist and I do not belong to any movement. You see, ‘Imagine’ was exactly the same message, but sugar-coated.” Adding that “because it is sugar-coated, it is accepted.” The manageable prose of life and death in Leary’s translation does much the same.